Union Square Before the Sparrows Came

In this newsletter: Worms on your face, reader mail, and yet another CDC advisory committee meeting that I watched so that you didn’t have to. If you’re not subscribed to this newsletter, you can sign up here.

Part I: Waiting for the Worms

Consider these lines from a privately-published 1939 memoir of a woman named Frances Nathan Wolff, recalling the Manhattan of her 1860s girlhood:

Fourteenth Street at this time was very beautiful. Rows of large trees stood on either side of the sidewalk. Unfortunately, this was before the time when sparrows were imported to eat the worms infesting the city trees. Consequently, as one walked along, a worm would often drop right into one’s face.

The house sparrow, according to my sloppy analysis of data collected by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is the most commonly-sighted bird in New York City, followed by the American robin, and then the pigeon, and then the European starling.

(It’s obviously strange that reported robin sightings surpass pigeon sightings, and I have no explanation, except that I suspect birdwatchers are more likely to lift their pencils for a robin eating a worm than for four pigeons tearing up a garbage bag.)

The sparrow’s dominance of the New York City skies is undeniable. Pigeons are more obtrusive, and with their size and their flapping demand more of our attention, but the house sparrow is everywhere; a brownish, cheeping mouse of the air, nesting in the crossbars of traffic lights, scrabbling at crumbs under a bench, sitting on the edge of a garbage can. You know this. You’ve walked down a block in New York City in your life. There are a lot of house sparrows.

(It’s worth mentioning here that the house sparrow, Passer domesticus, also known as the English sparrow, is not the only kind of sparrow in the world, and that some other types of sparrow — for example, the delicate and yellowish LeConte’s sparrow — Ammospiza leconteii, are quite lovely.)

To picture New York City without the sparrow takes an enormous imaginative effort. Let’s not be so ambitious. Let’s not even try for all of 14th Street, the block invoked by Frances Nathan Wolff in her memoir. Let’s just imagine pre-sparrow Union Square; 14th Street to 17th Street, Broadway to 4th Avenue.

Before the sparrow, the buildings around Union Square were lovely old houses; fading beauties that had once been the finest in New York City. There was a big hotel there, called the Everett House, and, at the corner of 15th Street, Tiffany & Co., which, before the sparrow, sold no china or glass, only silver and jewels behind a wrought-iron facade. The statue of Washington on his horse stood over the square, and there was a fountain, but Lafayette, sword in hand, had not yet sailed from Paris.

Before the sparrow, the rich rode where they would in the hooded four-wheeled carriages called barouches, while everyone else packed into the dirty, horse-drawn street cars that rolled north and south along tracks embedded in the pavement. Before the sparrow, sidewalk musicians played the parks; the cliched organ grinders with their monkeys, yes, but also harpists and violinists who strolled the streets. Before the sparrow, there were trees, and in those trees, there were worms.

Worms? Well, inchworms, which are caterpillars, and which, before the sparrow, were devouring the American linden trees shading Union Square, and 14th Street, and streets all up and down the island of Manhattan and out into Brooklyn and beyond.

And amidst all this, not a single house sparrow.

A brief and relevant anecdote: We went on a little hike one day this past summer. There was a strange sound in the woods that day; a pit-pat-pit that sounded like a drizzle, though the sky was clear. A passing sun shower, perhaps. Then we saw the caterpillars.

A clump on a tree trunk. Another clump on a leaf. Then another. Then a fat one fell fell on someone’s back, and we looked around and realized that the woods were absolutely infested with gypsy moth larva, and the pit-pat-pit sound was a rain of gypsy moth larva poop. Frass, it’s called. Little black balls of caterpillar shit no smaller than a ball bearing, dropping from the trees around us so steadily, and in such an enormous volume, that it sounded like a light rainstorm.

We ran.

The gypsy moth plagues that come and go across the northeastern United States are the fault of one man, a moth fancier named E.L. Trouvelot, who bred moths in his yard in Medford, Massachusetts. Trouvelot wanted to build a better silkworm, so he cultivated a great flock of millions of native silk-spinning Polyphemus moths, Antheraea polyphemus, thinking that with some work, they might prove superior to the finicky Bombyx mori as silk producers.

Trouvelot cross-bred his Polyphemus moths with specimens brought over from Europe, including, in 1869, a shipment of Lymantria dispar dispar, the European gypsy moth. The gypsy moths blew away in a storm, and 152 years later, their 152nd-great-grandchildren pooped on my head.

There is no one man to hold responsible for New York City’s house sparrows. There was, instead, an idea, propagated by 19th century ornithologists and other such experts, that house sparrows could rid the cities of America’s eastern seaboard of the various caterpillars and other such pests that had infested their trees in vast numbers, their populations exploding as deforestation and industrialization killed off their natural predators.

The people who introduced the house sparrow to New York City were trying to solve an inverse problem to the one that Trouvelot was in the process of creating. They knew that one thing that house sparrows like to eat is the larvae of the linden looper, Erannis tiliaria, a particular moth species that infested New York City’s American linden trees at the time. Linden looper larvae are little inchworms, and it was these inchworms that were falling on Frances Nathan Wolff’s face as she walked down 14th Street in her pre-sparrow girlhood.

The first house sparrow colony successfully introduced in New York City settled in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn in 1853. Afterwards, people brought thousands of house sparrows to New York through the early 1860s, mostly from Germany and England. New York City pampered sparrows; treating them as exotic visitors, a curiosity and a delight. Here’s a passage written around 1870 by a journalist named James D. McCabe, Jr., describing Union Square as the sparrows came:

Near the fountain is a thriving colony of English sparrows, imported and cared for by the city for the purpose of protecting the trees from the ravages of worms, etc. The birds have a regular village of quaint little houses built for them in the trees… Some of the houses are quite extensive and are labelled with curious little signs, such as the following: “Sparrows’ Chinese Pagoda,” Sparrows’ Doctor Shop,” “Sparrows’ Restaurant,” “Sparrows’ Station House.”

When Frances Nathan Wolff was born on Bleecker Street in 1856, there were virtually no house sparrows in New York City, and no gypsy moths in North America. Nor were there European starlings, nor carp. By the time she died, great flocks of sparrows and starlings, great plagues of gypsy moths, great schools of carp, spanned the continent, starving out native species and pooping on our heads.

Of course, a child born today on Bleecker Street will outlive all the flocks and the all the schools, all over the world, which sounds like a far worse deal.

As for the moth plagues, those will outlive us all.

Part II: Letters

Readers have been in touch to suggest additional diners for me to mourn, in addition to the five I listed in last week’s dispatch. They are correct; I have been remiss. Here is a brief addendum to the litany of defunct diners I shared last week.

E.J.’s Luncheonette, 83rd and Amsterdam

I don’t think I actually liked the grilled cheese at E.J.’s Luncheonette on 83rd and Amsterdam, but that was my order: Grilled cheese, maybe a pickle on the side? I don’t remember. I hope it came with a pickle. The whole shtick at E.J.’s was 50’s-style vinyl booths and aluminum-edged tables, and I wonder if what I feel for E.J.’s is authentic nostalgia for eating at E.J.’s, or rather a memory of that suggested nostalgia? Was E.J.’s any good? I’m not sure. I hadn’t realized E.J.’s was closed, actually, which was why I left it off the list. It is closed; it closed a decade ago, though there’s a restaurant by the same name on the East Side, which I think was what confused me. E.J.’s wasn’t technically a diner, but rather a luncheonette; a fine distinction that I’m not sure means much at all, come to think of it. Anyway, consider it added to the list.

Doris’ Café, 345 Market Street, Fort Kent Mills, Maine

The second neglected diner is a bit farther afield, about 500 miles northeast of all these New York spots, or ten hours by car if you don’t stop for gas or coffee or the toilet, which you probably will need to do. The first time I ate there, on assignment for the Forward, I flew to Bangor, rented a Chrysler sedan, and drove north up I-95 to Houlton, then farther north up U.S. 1 to the end of the road. This was during a strange and wonderful period at the Forward when the editors sent me on long, aimless trips on vague pretexts. Spain! Kentucky! Maine! The Kentucky trip was the nuttiest: The idea was to write about the Kentucky Derby, but that idea fell through, so instead I drove to Harlan and Middlesboro and down into Tennessee, and then all the way over to Mammoth Cave. I watched the Derby via simulcast at Keeneland, and then squeezed it all into a single story about the mine wars and slaveowners and also segregation, which was perhaps not a great idea, but anyway it’s here. The only food experiences in Kentucky that made an impression were a frightful pizza in a city called Hazard, and finding a very large metal screw in my hamburger at a restaurant in Lexington. (I stared at it, wondering if it was a prank. Then I hid it under the french fries and called for a check.) On the Maine trip I sought out diners, and in Fort Kent found the most perfect diner on the eastern seaboard. In the extremely long article I wrote about the visit to Maine, I said this about Doris’ Café:

The diner is on the edge of town, in a building it shares with a small post office. I saw a fox run through the field across the road as I stepped inside. Regulars’ mugs hang on pegs by the door, and French toast costs $1.90. I had two eggs with homemade bread and some tea.

I don’t know why I undersold it like that. I think I thought my writing was supposed to be spare? Doris’ Café (I know that’s how they rendered it, because I own a Doris’ Café t-shirt in dark blue that I wore so often it now has a huge hole in the armpit and I can’t wear it out of the house anymore) was fantastic. The place was small, it smelled great, half the tables were full of retired potato farmers who met there every day for breakfast, and all the conversations were in Acadian French. Doris’ Café was sold to new owners in 2019, and sometime over the past year I heard it had closed. Its listing on Google has that ominous red “Permanently closed” banner beneath it, and my worn-out t-shirt seemed to have transformed into a precious relic. Yet all may not be lost: Per a Yelp review from July of a place called Memere’s Kitchen at the same address: “Doris' is now Memere's.” Good news. I’ll let you know how it compares next time I go north.

But that’s it. No more addenda. Those are all the diners that I miss.

Part III: All The News

Looking for a catch-up on the week’s pandemic news? I did another Barron’s Live podcast this week, though fair warning: We recorded it on Thursday, so Friday’s news on boosters for all adults is not included. It hasn’t posted yet, but you can find it here when it does, or subscribe to “Barron’s Live” on iTunes.

But if you want to read about Friday’s news on boosters for all adults, never fear! Here’s the latest edition of “I watched the CDC advisory committee meeting so you don’t have to.” There was actually a bit of bureaucratic drama. A paragraph:

The CDC’s advisors met amid a messy booster rollout that increasingly threatens to undermine the credibility of the U.S. federal health regulators… The FDA and CDC limitations on boosters for adults under 65 have been widely ignored by state and local health authorities.

I also talked to the Pfizer CEO this week, and asked him if his company has a responsibility to ensure its vaccine is being distributed fairly. And I wrote plenty of other stuff, but you know how to find it if you’re interested.

Part IV: Words of Advice

Frances Nathan Wolff’s wedding dress is photographed here.

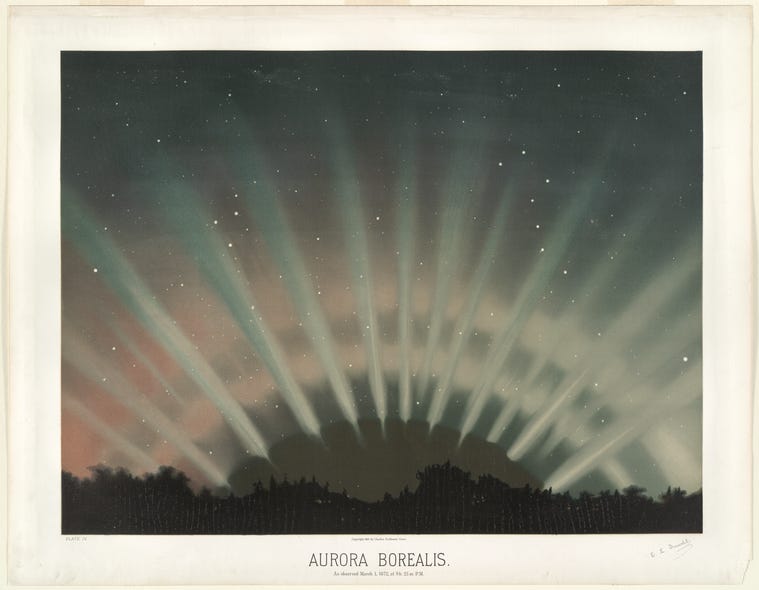

This spectacular drawing of the northern lights is by E.L. Trouvelot, the idiot described above who is responsible for the gypsy moths that pooped on me in the woods this past summer. Here is an extraordinary drawing he made of a meteor shower, and here is one of the Great Comet of 1811, all from the collection of the New York Public Library. Caterpillar shit and cosmic splendor; the duality of man.

The only other video ever posted on YouTube by the account that posted last week’s extraordinary clip of Carol and Babs talking about Mel Brooks, and then inexplicably breaking into the song about the cloak makers’ union, is an incredible piece of found art posted eight years ago titled “Crap.” The filmmaker seems to have brought a piece of fake poop on a trip to Las Vegas, left the fake poop in a hallway of some casino, taken blurry pictures of people walking past the fake poop, and then strung the blurry pictures together in a slideshow played over the 2011 novelty dance song “Party Rock Anthem” by the uncle/nephew duo LMFAO. It currently has 26 views. Go be the 27th!

One more Misfits cover. I’m running out of Misfits covers.

That’s all I’ve got!