What is the Scariest Animal?

In this newsletter: Preliminary thoughts on a pressing question. Plus, a podcast update on the pandemic and, as always, some words of advice.

Part I: Fearsome Beasts

The scariest animal is a mouse-sized cockroach flying at you from seven feet up your bedroom wall. The scariest animal is a polar bear. The scariest animal is a very large rat inside of your apartment. The scariest animal is a very large rat inside of your toilet bowl. The scariest animal is a very large rat meandering down the sidewalk in the middle of the afternoon, bumping into stroller wheels. The scariest animal is a deer tick that you find on your leg while you’re sitting on your couch, and then you fumble it and it gets away and you know it’s in the couch somewhere but you can’t find it. The scariest animal is an elephant. The scariest animal is a bed bug. The scariest animal is a wild boar the size of a Fiat.

Early in the pandemic, one popular genre of viral news stories tracked animal incursions of human spaces left vacant by the lockdown. You had goats browsing the Welsh village of Llandudno, foxes in the streets of Ashkelon, dolphins in the Bosphorus, sea lions lounging around the beach resorts of Argentina, peacocks in Mumbai, and boars in downtown Haifa. Nature, as the meme went, was healing.

Two years later, the notion that these incursions were somehow salubrious seems quaint, an obvious delusion born of a shared necessity for a redemptive story to tell about those blighted months; a need to believe that, even if we were all miserable, at least the boars were having fun.

That leaves unresolved the question of why those animals were sniffing around. I believe it was reconnaissance.

There’s an essay in John Jeremiah Sullivan’s 2011 collection “Pulphead” called “Violence of the Lambs,” in which Sullivan predicts that armies of animals, led by chimpanzee generals and dolphin admirals, will wage war against the humans. At the end of the essay, Sullivan reveals that he’s mostly joking; his main source is made up, his reporting trip invented. Sullivan enjoys the notion that animals might turn on us, but he doesn’t believe it.

It’s time to reconsider his essay in the face of new evidence.

I’m not arguing that we should be preparing for some Planet of the Apes-style conflict. What I am saying is that the list of animals that Northeastern apartment-dwellers legitimately need to worry about is getting longer every year, and that it’s all got to be heading somewhere.

Bed bugs, for instance. Before 1999, a person living in the United States of America generally did not need to think about bed bugs. In 2009, one out of every fourteen adults in New York City reported a bed bug infestation.

Or ticks. Deer ticks, in the mid-1990s, were a thing you might have worried a bit about if you lived in one of a few counties in New England. They’re now endemic across the eastern U.S., spreading westward by the year, and, by most accounts, growing more and more numerous.

I hesitate to even mention rats, for fear of frightening you away, but we must face facts: The rat population in New York City is unbelievably, extraordinarily, world-historically huge. Five, ten, twenty years ago, you might have seen a rat or two on the subway tracks. These days, it’s notable when I leave the house and don’t see a rat.

My own personal theory is that this is largely the fault of those New Yorkers who took up feeding the park squirrels as their pandemic hobby. The lockdown disrupted the rats’ food sources, so they ventured out to find something else to eat, and came across the unshelled peanuts and bird seed and whatever else these antisocial lunatics were tossing around the park, and it emboldened the rats: Peanuts are nice, but what else is out there? And so they set out to explore, and realized that this city of eight million people just leaves its garbage out on the sidewalk, in thin plastic bags you can bite through in a second. And, yes, of course rats have always eaten from the sidewalk garbage bag piles, but it’s never been like it is now; each pile its own writhing nest of rat-flesh.

Anyway, I just want you to skim this article about the fear that monkeypox might establish itself in new animal populations, and how that would basically be extremely bad, and then just think for a moment about the millions (tens of millions?) of rats living in and over and around us. Or actually maybe don’t.

The megafauna, too, are coming for us. Before 1980, there were zero black bears in the state of Connecticut; there are now over 1,000. In northwest New Jersey, the black bear population more than doubled between 2018 and 2020. Great white sharks have attacked five people on Cape Cod since 2012, after only attacking three people in the whole state of Massachusetts during the entire 20th century. Just in the last few days, sharks attacked two lifeguards off of Fire Island and one swimmer off of Jones Beach.

These various encroachments are, to a degree, coincidental, each driven by its own various causes: The warming climate, the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act, the advent of inexpensive air travel, the overuse of DDT. Taken together, though, they send a message. You can mow your lawn as tight as you like, you can close your windows and blast the air conditioner, you can live sixty feet in the air in a newly-built luxury apartment with no cracks between the baseboard and the flooring. The animals can still get to you, and when the time comes, they will.

Which leads us back to the initial question: Which animal is the scariest? Of all our natural enemies, which should worry us the most?

For the purposes of this exercise, we must limit ourselves to the kingdom Animalia, with particular reference to members of the phyla Arthropoda and Chordata. We’ll leave aside P. falciparum and its fellow malaria-causing protozoa, all the various streptococci and staphylococci, and those other microscopic and submicroscopic nightmares: Vibrio cholerae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Yersinia pestis, Clostridium botulinum, Bacillus anthracis, the variola virus, the Ebola virus, the Marburg virus, SARS-CoV-2, and so on, and so forth.

A totally rational approach to the problem would necessarily lead to the conclusion that the scariest animal is the mosquito, the creature responsible for more human death than any other multicellular organism. Fear, however, is not always rational, and I don’t feel my stomach drop out when I see a mosquito buzzing towards me across the lawn.

The scariest animal is the creature whose potential presence inspires dread, even if it’s actually nowhere in the vicinity. Shark advocates like to pretend that “Jaws” invented the notion that sharks are scary, but as anyone who has ever looked out over the ocean on an overcast day and knows, the fear of sharks is hard-coded into the human amygdala. Sharks are so scary that a person can summon a terror of sharks even when looking out over an inland lake, if it’s deep enough, or, on a really grim afternoon, a large backyard pool.

Sharks, however, are not the scariest animal, because sharks are easy to run away from. The thing about sharks is that you can avoid them pretty well if you stay out of the ocean. All the GoPro videos I’ve ever seen of sharks chasing spearfishermen end with the spearfisherman climbing into his boat and the shark impotently splashing away, foiled like a Scooby Doo villain.

It’s tempting, when considering scary animals, to get sidetracked by Snapple bottle cap-style facts about Amazonian catfish that can swim up your urethra, or Australian jellyfish that can stop your heart. These animals are scary, but they are not the scariest animals. The scariest animal is a terror and a horror and, at the same time, an object of wonder and beauty; a marvel of selection and evolution. The scariest animal is, in fact, the mountain lion, also known as the cougar, or the catamount. It’s all the same thing: A feline that hunts elk and can jump 15 feet straight up in the air from a standstill.

A forest inhabited by a mountain lion is like an ocean inhabited by a great white shark: Look out across the trees on an overcast morning, imagine for a moment the mountain lion lurking beneath their canopy, and feel that shapeless horror grip your throat. Mountain lions stalk their prey, hiding in the undergrowth and then leaping to clamp their jaws around the back of their victims’ neck, dragging it to the ground and severing its spinal cord.

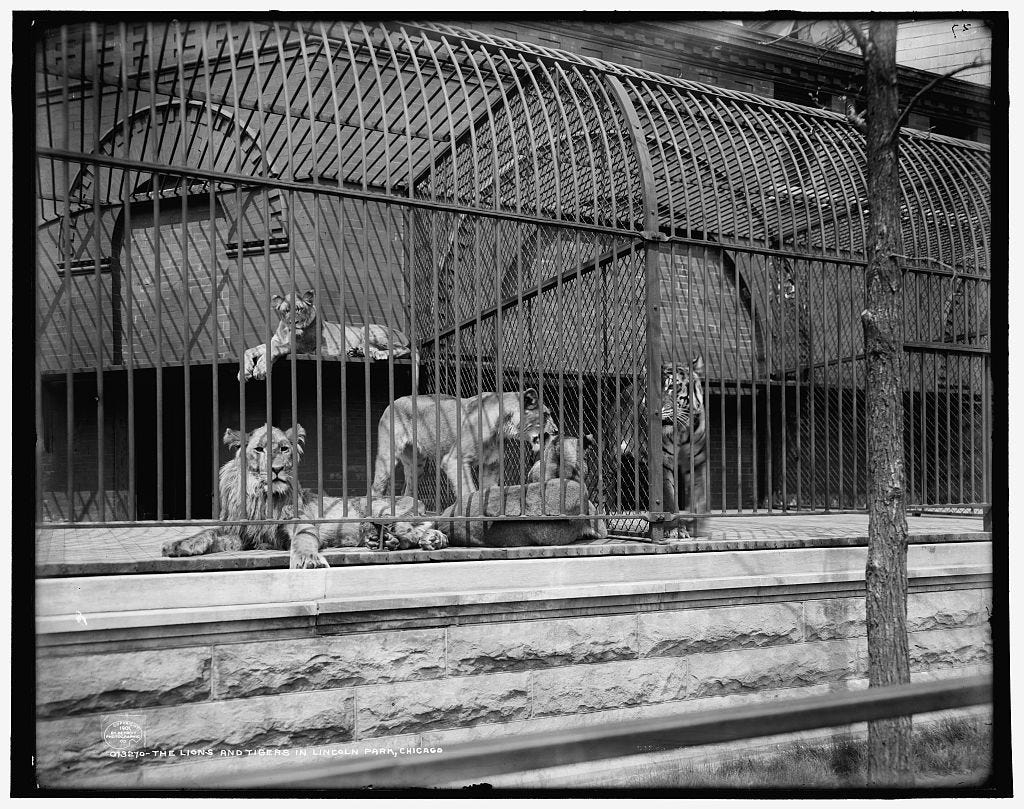

There’s a zoo in New Jersey with a mountain lion who just paces back and forth along the front of its enclosure all day, and you can tell from looking at its eyes that it’s thought through exactly how it would kill you.

Mountain lions are extinct in the East, except for in south Florida, which has a small native population. That’s the theory, at least. In practice, it’s less clear.

In 2011, residents in the vicinity of Greenwich, Connecticut, began seeing mountain lions. No one believed them until a Hyundai ran over an 140-pound mountain lion one night in June on the Wilbur Cross near Milford. The state later determined he had walked to Milford from South Dakota. Officially, since the Hyundai did its work, there are no wild mountain lions in Connecticut, but people still see them, sometimes. This year and last, there have been repeated sightings in New Canaan, not far from Milford.1

That’s what’s scary about mountain lions. The power of an apex predator without any of the omnivorous reasonableness of the black bear, mixed with the uncertainty of the shark. Is it out there? If it was, you wouldn’t know it. Maybe it’s not, but if it isn’t, why is that paw print so big? How sure are you that that was a bobcat? And why is there a deer carcass up in that tree?

So that’s the scariest animal, as far as I’m concerned.

Or, actually, it might be a banded sea krait. Those things are freaky, my god.

Part II: A Pandemic Podcast

On the Barron’s Live podcast this past week, I talked about the latest on the pandemic, plus other healthcare industry news: Pfizer’s Covid-19 vaccine price bump, the monkeypox vaccination campaign, the coming replay of the Aduhelm controversy, and more. You can listen here.

Also in Barron’s, I wrote about how the biotech company Intercept Pharmaceuticals is taking another crack at a drug the FDA rejected two years ago, a new drug pricing bill in the Senate, and that Aduhelm redux, among other things.

Part III: Words of Advice

You prefer the Yiddish “Fiddler” to the original English, you say? But have you sampled the Japanese production?

I should note that the John Jeremiah Sullivan essay referenced above was originally published in GQ, accompanied by a photograph of a screaming lamb with a bloody snout.

The entire above essay was inspired by an email from our building management the other day telling us that there were termites in the basement, potentially, which really threw me for a loop: It’s all cement down there, we live in New York City, what the hell. Turns out they weren’t termites, so, uh, sorry about all the above insanity. I take it back. Animals are fine. We’re fine. It’s all fine.

If you hated “Gazte Arruntaren Koplak,” the Basque-language (novelty?) (parody?) (cover?) song I sent last week, you’ll hate this song by the same band even more.

That’s all I’ve got!

Why does Connecticut have a New Canaan and a Canaan, and also a New Milford and a Milford?